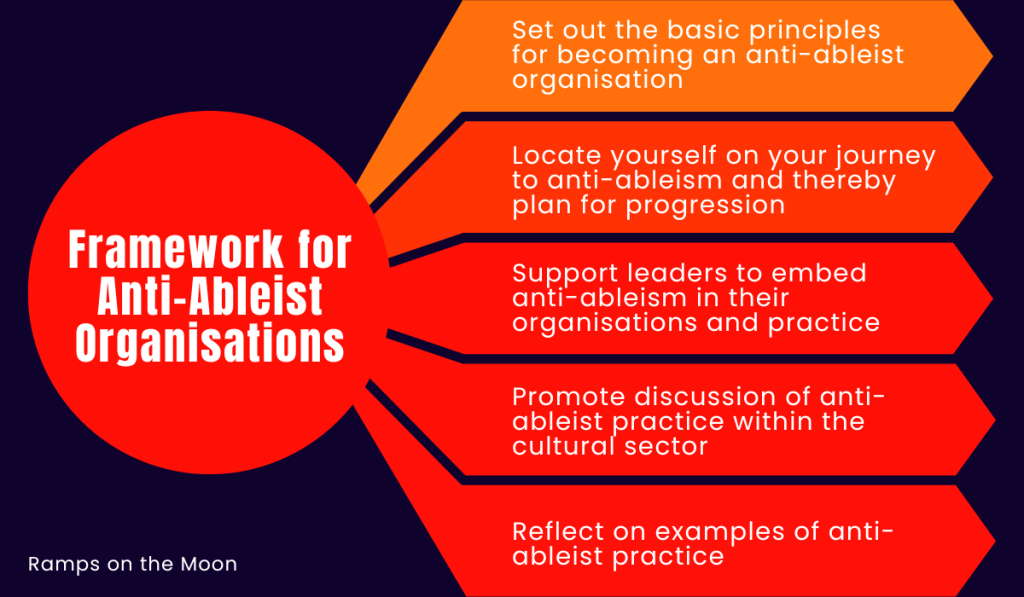

this framework has been created to:

Set out the basic principles for becoming an anti-ableist organisation

Enable you to locate yourself on your journey to anti-ableism and thereby plan for progression

Support leaders to embed anti-ableism in their organisations and practice

Promote discussion of anti-ableist practice within the cultural sector

Reflect on examples of anti-ableist practice

The Case for an Anti-Ableism Framework

Why aim to be an anti-ableist organisation?

Ableism:

Ableism is the systemic discrimination, prejudice, and social stigmatisation against disabled people, and this means that disabled people are disempowered and disenfranchised. Ableism privileges certain types of bodies and brains and favours certain ways of being in the world. Society equates the favoured ways of being with being ‘healthy’, thereby pathologising those who don’t fit.

Anti-ableism is the practice of actively challenging ableism. It means advocating for equal rights and promoting the understanding and respect for the experiences and requirements of disabled people. Anti-ableism seeks to dismantle systemic barriers and foster environments where disabled people can fully participate, lead, contribute and flourish. In other words, an anti-ableist organisation is open to allowing itself to be fundamentally changed by disabled people’s voices.

NB ‘Disablism’ generally refers to direct discrimination against disabled people and does not necessarily acknowledge systemic or institutionalised discrimination.

Intersectionality:

Intersectionality is a framework for understanding how various forms of social inequality, such as ableism, racism, sexism, classism and transphobia, overlap and intersect to create unique experiences of oppression and privilege for individuals and groups. Kimberlé Crenshaw used the term in the late 1980s to describe the way in which people have multiple, interconnected social identities that shape their experiences and perspectives. The notion of intersectionality draws attention to the ways in which these intersecting identities compound and complicate the impact of discrimination and marginalisation.

In cultural organisations, funding policy can encourage us to think in terms of segregated identities and characteristics. In fact, it is important to recognise that many disabled people experience, and identify with, multiple characteristics.

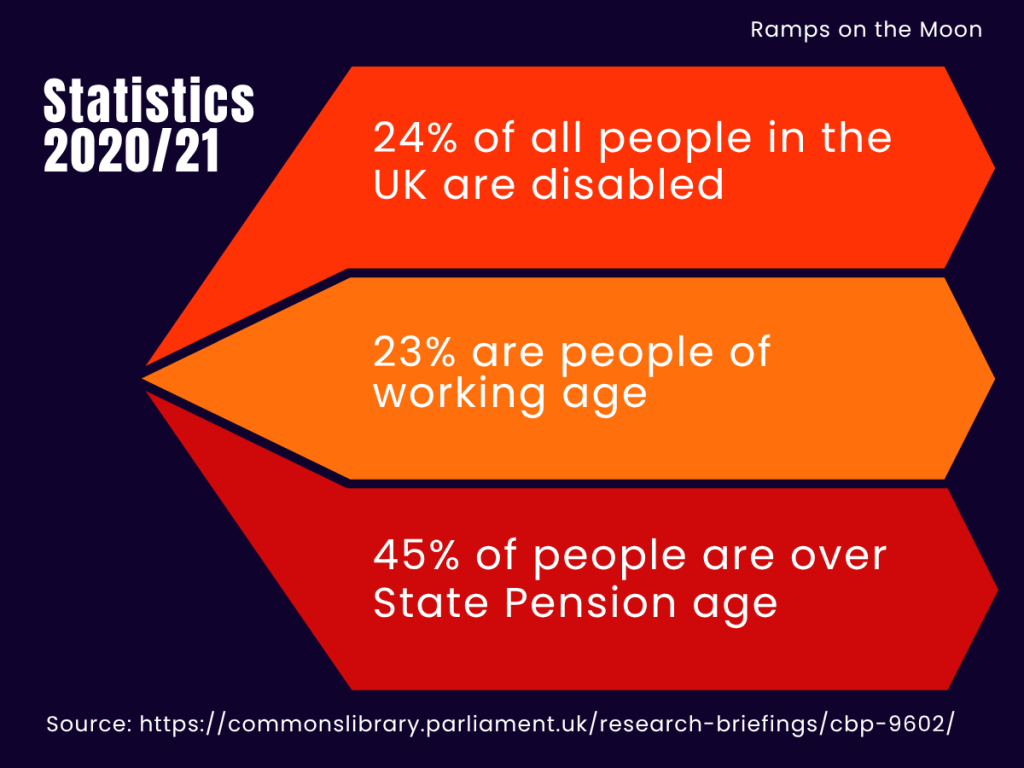

Statistics

Figures for the 2021/2022 financial year[1] were that disabled people accounted for 24% of all people in the UK, 23% of people of working age, and 45% of people over State Pension age.

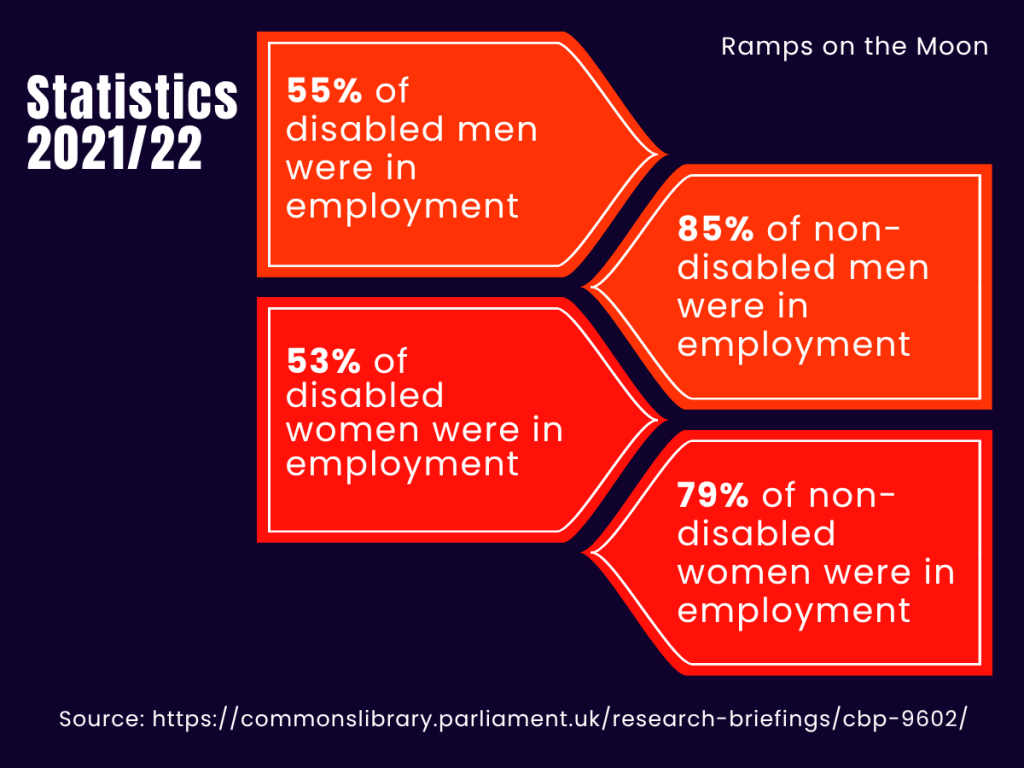

In 2023, 55% of disabled men and 53% of disabled women were in employment, as opposed to 85% and 79% for non-disabled men and women, respectively.

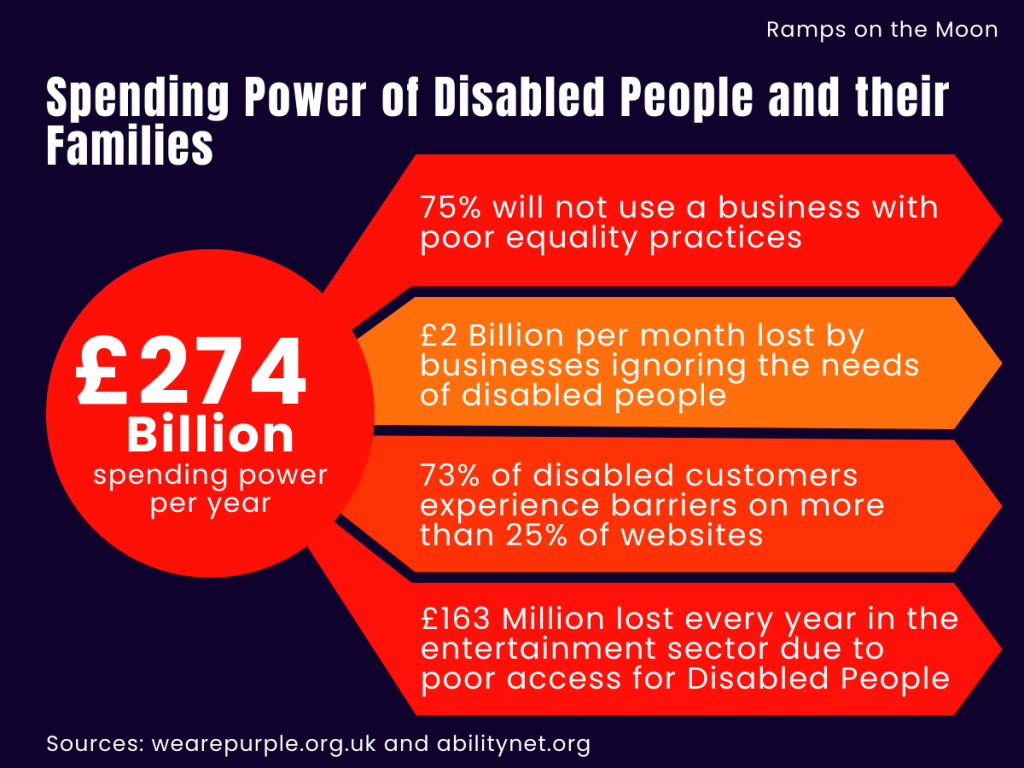

Purple reports[2] that in 2020, the annual spending power of households that include a disabled person was £274 billion.

Around 8% of disabled people use wheelchairs[3].

Cultural enrichment

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (sic) states that disabled people should be able to participate in cultural activities; it goes further and states that disabled people should “have the opportunity to develop and utilise their creative, artistic and intellectual potential, not only for their own benefit, but also for the enrichment of society”[1].

Sir Iain Lobban, when he was Director of GCHQ and speaking at an event to celebrate the contribution of Alan Turing, said:

“An agency requires the widest range of skills possible if it is to be successful and to deny itself talent because the person with the talent doesn’t conform to a social stereotype is to starve itself of what it needs to thrive”.

[1] https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-30-participation-in-cultural-life-recreation-leisure-and-sport.html

Financial considerations

75% of disabled people and their families report having decided against using a particular business because of their poor equality practices[1].

The reality is that, if an organisation is not serving disabled people, not only will it potentially lose theirs and their households’ custom, but also the custom of any friends or other contacts that they share their experiences with.

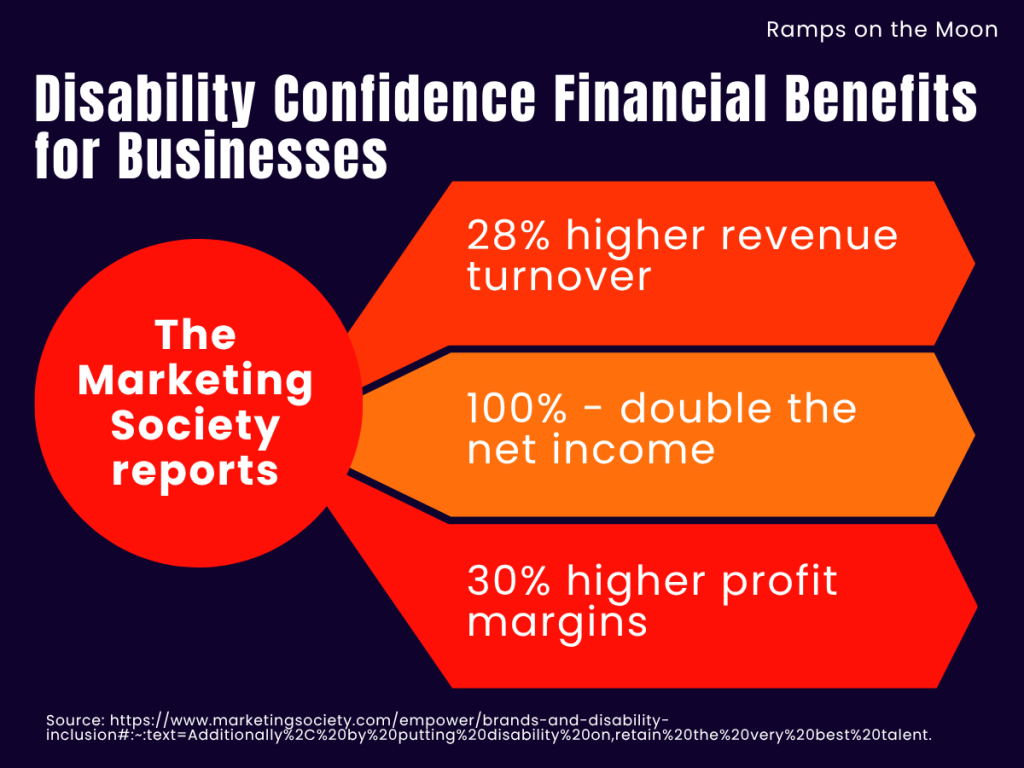

The Marketing Society claims that, on average, companies who demonstrate disability confidence achieve 28% higher revenue, double the net income and 30% higher economic profit margins than those who do not[2].

£2 Billion per month is lost by businesses ignoring the needs of disabled people.

73% of disabled customers experience barriers on more than 25% websites.

£163 Million per year is lost in the entertainment sector due to poor access for Disabled People.

It’s important, also, to say that there is no ceiling to the amount of compensation that can be awarded when an organisation is shown to have failed to meet their duties under the Equality Act (2010).

[1] https://abilitynet.org.uk/news-blogs/businesses-are-missing-out-purple-pound-says-scope

[2] https://www.marketingsociety.com/empower/brands-and-disability-inclusion

[3] https://wearepurple.org.uk/the-purple-pound-infographic/

Your organisation’s values

Many organisations’ stated values are about welcoming everybody or being for everybody. Moving towards anti-ableism will support the organisation to realise those values. Not only will it ensure that disabled people are playing an active part in the organisation, but many of the measures that are taken with anti-ableism in mind, will benefit others who are socially and culturally excluded or marginalised.

A Note on the Legal Context

The Law has not been included as part of the case for anti-ableism because we should be able to take legal compliance for granted, and it therefore sits outside the 4 phases of this framework.

An Organisational Approach

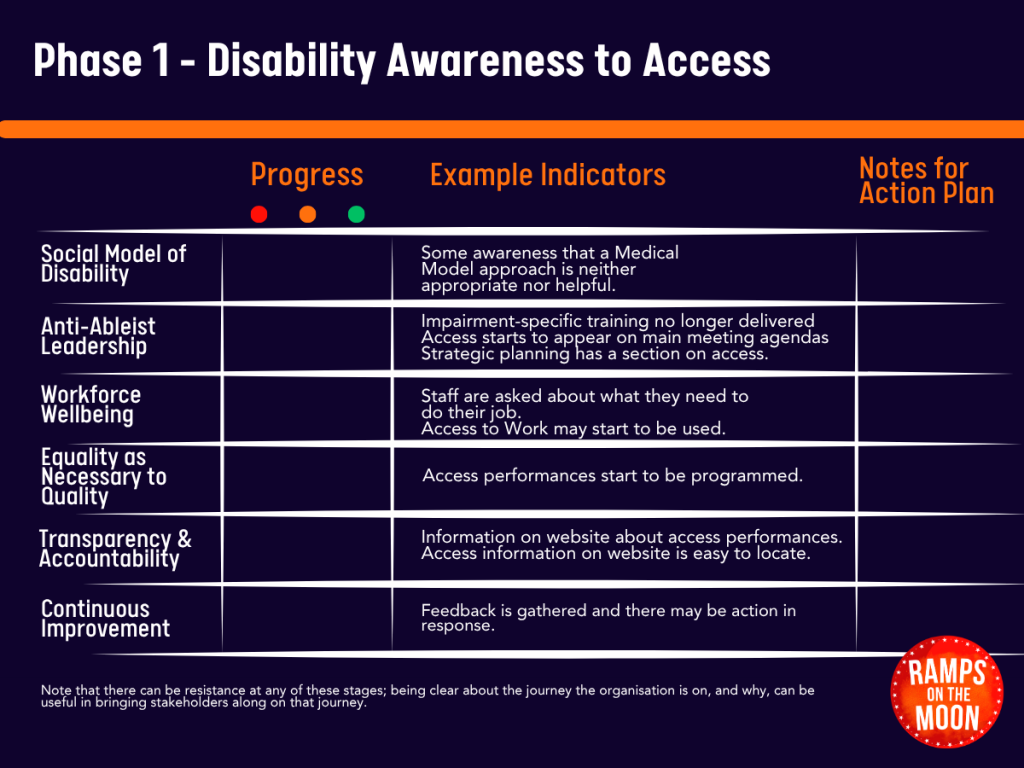

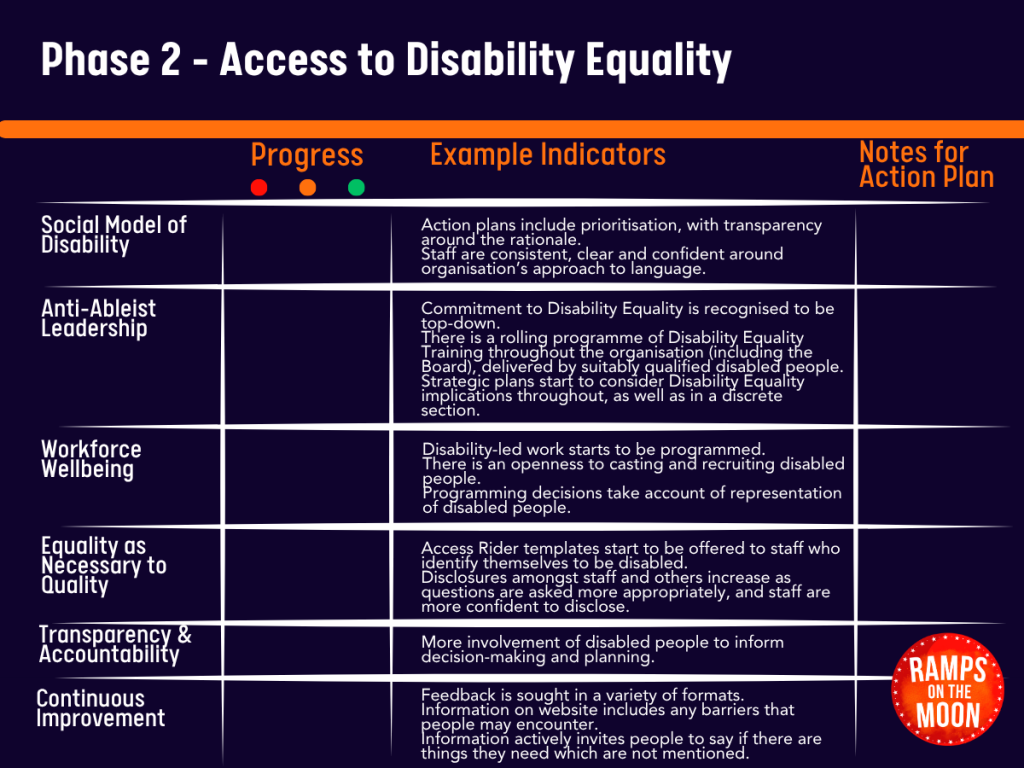

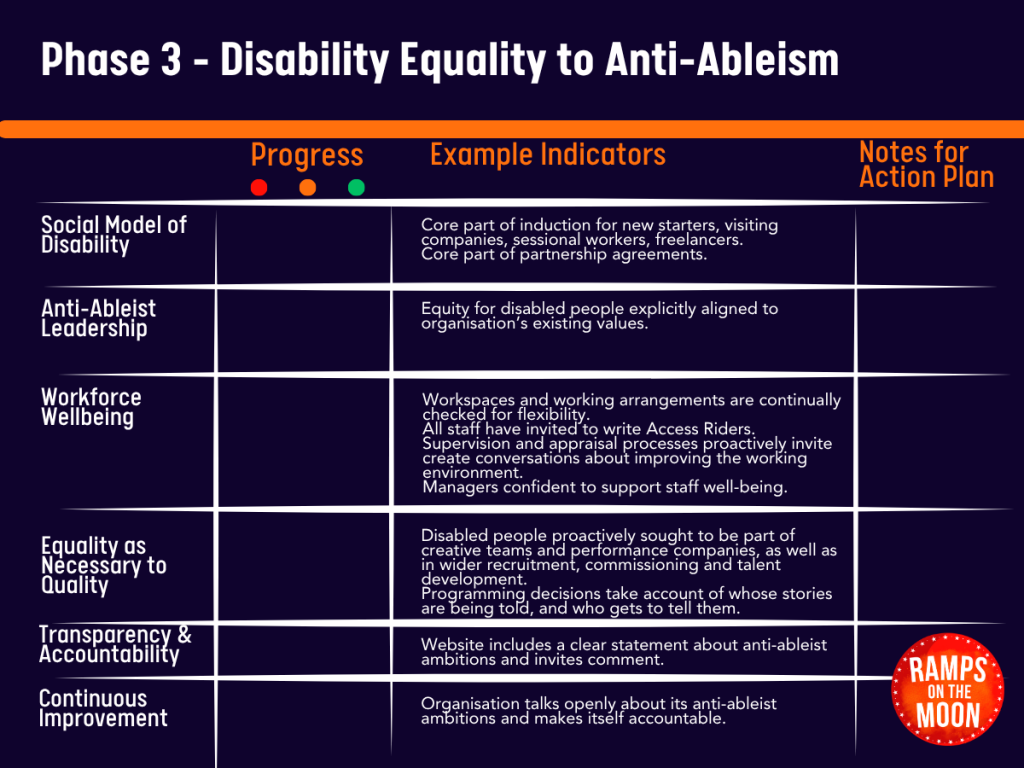

We have identified 6 core commitments which underpin embedded anti-ableism:

1.Adherence to the Social Model of Disability

2.Anti-Ableist leadership

3.Workforce wellbeing

4.Equality as a necessary condition of quality

5.Transparency and accountability

6.Continuous improvement

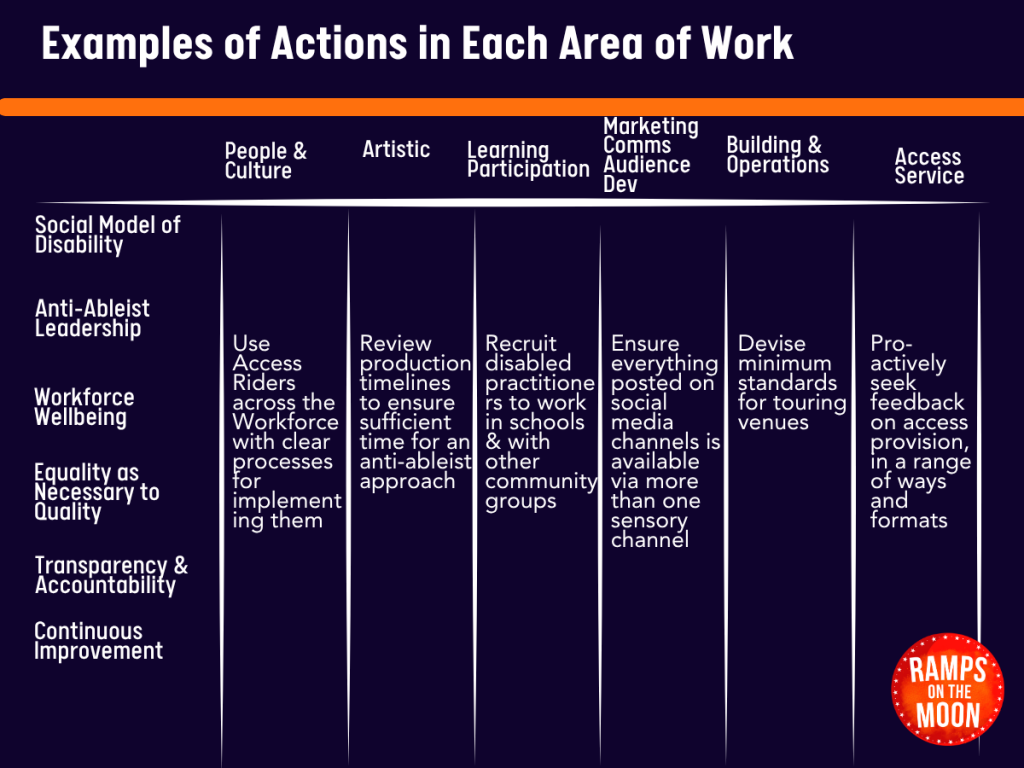

And 6 key areas for anti-ableist practice within an organisation:

1.People and Culture

2.Artistic and Production

3.Learning and Participation

4.Marketing, Comms and Audience Development

5.Buildings and Operations

6.Access Services

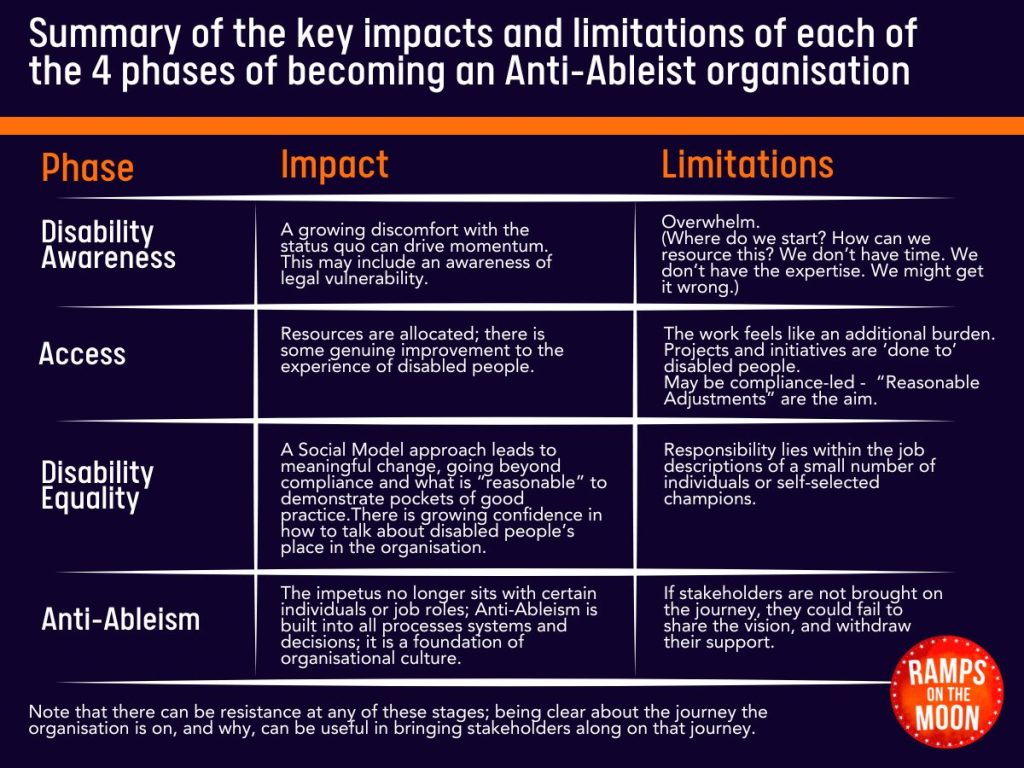

We suggest 4 phases of becoming an Anti-Ableist Organisation.

1. Disability Awareness – Outreach

Individuals within the organisation recognise that disabled people are not represented in the workforce or audiences. Thinking is likely to be based on the Medical Model and the aim is to ‘provide for’ disabled people.

A specific incident might alert leadership to the need for information, training, and / or external support.

Training may be a generic equalities course, an impairment (condition)-specific course, or Disability Awareness Training delivered by someone who is not themselves disabled.

There is likely to be a period of overwhelm as individuals and teams struggle to turn their awareness into specific action.

2. Access – Open Doors

Action plans start to be generated, but there is little clarity around how to prioritise.

Teams may seek expertise from outside the organisation. Feedback may be sought from disabled people about their own specific and individual experience of the organisation.

Some teams and individuals develop a real commitment to making change. This usually focuses on provision for disabled audiences and participants.

This is an ad hoc and ‘bolt-on’ approach. Disabled people are allowed, even welcome, to contribute and participate but the organisation remains unchanged in terms of policies, processes, and culture. Essentially, disabled people are expected to fit into an ableist organisation functioning in an ableist society.

Change is characterised by adding to or tweaking existing provision; systems and processes remain unchanged. In other words, the changes relate to what parts of the organisation do.

3. Disability Equality – Backstage Pass

The impetus to move towards Disability Equality can come from a number of sources: for example, individuals or teams in the organisation may gradually become dissatisfied with the ad hoc approach, recognising its limitations; or there may be pressure from elsewhere in the sector; or someone new joins the organisation, and brings an understanding of disability equality; or someone in the organisation has a chance encounter with a disability advocate; or funding requirements change.

This leads to a more strategic approach to planning.

The Social Model of Disability becomes more prominent on the organisation’s radar and a good Disability Equality Trainer / consultant is engaged. There may be a good deal of emphasis on access performances, and disability-led work may be programmed.

Generally, adjustments for audiences are more developed than for anyone working in the organisation. Access tools are more integrated within performances. Programming takes more account of the stories that are told. More disabled people are involved in the organisation including staff and freelancers.

Real changes can take place, based on the Social Model of Disability, and may include some review of systems and processes. In other words, changes relate to what the organisation does.

However, the shortcomings of Disability Equality start to show, and the inefficiency of a project-led approach becomes apparent.

4. Anti-Ableism – Foundations

The organisation takes a pro-active and systemic approach to equity for disabled people. The organisation is no longer based on traditional, ableist approaches, but recognises the need to challenge assumptions about the way things are done and who can do what.

The organisation builds equity for disabled people into its processes, timeframes, and decision-making, and starts to critique the ableism inherent in its own culture. The organisation starts to inch ahead of its peer organisations in terms of what it expects of itself, and it is recognised as an industry leader.

Leaders are less afraid of mistakes than they are of inertia and inequality.

Disabled people already in the workforce become more confident in discussing their access requirements, and more disabled people work in and with the organisation. This creates a virtuous circle.

There is a commitment to questioning accepted aesthetics and checking where standards of artistic excellence are based on ableist values. The organisation’s work explores an anti-ableist understanding of quality.

In other words, change relates to the organisation’s core identity, which means that equality for disabled people feels less like an exception, an add-on or an extra draw on resources.

Connections are made between disability equity and a more general approach to well-being in the organisation.

Note that there can be resistance at any of these stages; being clear about the journey the organisation is on, and why, can be useful in bringing stakeholders along on that journey.

For a full PDF version please download this document:

This Framework for Anti-ableist Organisations report was created by Ramps on the Moon in March 2025.

© Ramps on the Moon 2025. All rights reserved.

No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise – without prior written permission from Ramps on the Moon.

Quotations from this report are permitted, provided that Ramps on the Moon is clearly credited as the source.

For further information or enquiries, please contact us via this website.